The Colonel (RIP)

Last month the local community said goodbye to a figure of renown, Col. Jack Van Loan, USAF (ret.), a true friend to our neighborhood, and to me personally. He will be missed. Here is a brief essay about our relationship.

One of the Five Points water features Jack Van Loan helped us get built.

When I first met the man I would come to think of as The Colonel, I was a freshly seasoned but still somewhat green retailer, an academic refugee from an earlier career traded for the independence of entrepreneurship. Learning curve is an insufficient term.

With this change, and having been a leader now in two different industries, I started expressing myself about how I thought things ought to be done in the neighborhood of Five Points near the sprawling, venerable old University of South Carolina.

Word came back to me that I should put my civic leadership where my mouth was by running for the neighborhood association’s Board of Directors, a sort of star chamber of duly elected minds keen on setting the course of the commercial area for the boon and benefit of all. I did so.

Having won the election I became initiated and seated among power players I barely knew, and who all had their own agendas and trips going on way above my pay-grade, as a man like Jack Van Loan, USAF ret., would put it. I listened; I learned.

Controversies, then as now, abounded, but having an internationally known American Vietnam War POW and eventual returnee at war’s conclusion on one’s team gave us legitimacy, and entrée into the offices of fawning congressional critters who counted on Jack’s various civic organizations back home, within which opinion-makers of The Colonel’s stature could make or break support levels come election time.

This key role in the life of our community led directly to assistance from figures like the late Senator Ernest F. Hollings in securing funding on a much-needed streetscaping project that consumed the middle of the first decade of this century. The process began and ended with two lovely water features where for decades had been scuffed curbs; red brick pavers and a motif of forest green lampposts, bollards and waste receptacles added further aesthetic improvements, as did the burial of many overhead power lines. The Five Points neighborhood, over a hundred years old and the original suburban shopping district to downtown and nearby housing developments, remains an exemplar of what other parts of this capital city with centuries of history behind it still need to achieve.

Jack Van Loan wasn’t the only player, here. The machine included many other area stakeholders and political players at the level of city, county and state, and all deserve their due at such time as some other author deigns to write a blog post about what they meant to him personally. But as far as our little neighborhood association went, The Colonel’s status as an honest-to-God American hero offered serious grease for our wheels. No question.

After a term, I dropped off the Board. I didn’t have any political power or leverage, only casual friendships, and didn’t feel a part of the process. I also had a burgeoning writing career, a long-held ambition, finally starting to simmer and bubble, and felt my energies better served by focusing on that and the business I owned with my wife.

A few years later, however, I’m pulled back in over concerns and issues the passage of time has covered and obscured with sand. Having become a novelist by then and beginning down a road of teaching, as well with ten years of business ownership under my belt, my second term would nonetheless entail a higher level of engagement on my part, and involved a much closer working relationship with The Colonel.

After a year of activity in which I was awarded Most Active Board Member of 2008, I accepted the nomination to become the Association’s president, but only after a modicum of arm-twisting and drink-buying, which in those days I must sadly report comprised the lion’s share of my attention, at least as much as writing, the business, or the Five Points Association. That would change. It had to. Otherwise, I might not be here writing this.

Despite my own personal travails, I feel I managed to serve with honor during a contentious time. I put on a suit and made speeches and went to cocktail functions and found myself hobnobbing with power players of all stripes, often, and because of, The Colonel’s recommendation that I be paid attention to; that I presented a figure of consequence and dignity as worthy of respect as his own. I was the face of 5 Points in that guise. And due was paid. We were described to me, then, as ‘the most influential neighborhood association in the city.’ And they had seen fit to embrace some hippie artist as its leader.

Col. Van Loan and the Author at the Association holiday party, December 2008.

Now, as good as that felt, it was not entirely or at all deserved, not held in contrast with The Colonel, a man who’d shown such fortitude and courage in the face of his time in captivity, and before that flying combat aircraft in and out of war zones on a bone-chilling 74 missions before the fateful one that brought him down in the hands of an enemy who would go on to torture and confine him for nearly seven long years. I had been a university archivist, a T-shirt salesman, an author and sometimes journalist; a Deadhead, a psychonaut and seeker. An interesting life for myself, but not precisely ‘serving’ in the way Jack had. Serving the muse, perhaps.

With all this in mind, I viewed my term on the Board under his tutelage this time and serving as his ‘wing-man’ on various missions of fundraising and politicking and meeting facilitation, as my own stab at community service, in my own small way. Doing so in the shadow of a man of unimpeachable character, drive and influence like The Colonel, who clearly felt our efforts worthy of everyone’s time, made my decision to serve and lead an easy and edifying one.

But again, service failed to fully pull me away from a career and life-track that had been going on for over thirty years, and with a contract on my second novel at hand and any number of other creative threads beginning to cohere, I left the Board with handshakes all around, the most hearty from Jack himself.

“I was honored to serve alongside you,” I never failed to tell him in the years since, “and I think of those days still with fondness.”

“Well, it’s an honor to be thought of!” he would reply.

Of late those visits had been relegated to the occasional neighborhood function, where he would appear, more and more immobile to the point of needing a wheelchair, but still regal and dignified in his emeritus status as a man of importance and legacy; there, I would seize my moment and make my mention of appreciation. He never failed to respond in kind. At this point, we had both become emeritus presidents, with our presences now largely symbolic and irrelevant. Thank you for your service.

During the period in which that same neighborhood association dedicated a small plaza and statue to Colonel Van Loan, I was at my most arm’s-length position of my adult life with the goings-on of the neighborhood, its politics, even my own family business while I blazed through ten novels, fifty short stories, who knows what else on the path to where I have landed. That day I found myself on the outskirts of the crowd, far from the Colonel, as a parade of politicians and notables made their speeches, and other ‘wing-men’ extolled the virtues of the man and his influence. I congratulated him before the ceremony, but made my way back to my business and whatever responsibilities lay ahead without further hobnobbing. Good for him, I thought, and good for them. They built it; I came. But I had nothing to add. It was fine.

Earlier this year I began hearing that Jack faced a steeper decline, and before long the news came that he had passed away. I felt an aching pang—another loss of figures to whom I owed much. My list ever lengthens, but whose doesn’t once they age into their 50s?

This time, however, this blow came right as I returned to the Board for a third go at civic duty. With retirements and a variety of other issues contributing to a vacancy not only of a seat but a potential loss of what’s known as ‘institutional knowledge,’ I now find myself immersed, at least for the moment, in a yet different role from either of the first two times of service—now, I seem to be playing the unlikely and alien part of elder statesman, in a sense. Or at least elder enough to retain a few of the secrets of the local potlatch ceremony, which must be passed down from those who have served to those who will carry on.

It was in this role I found myself one afternoon standing at that memorial to a man I had respected and loved, from whom I had learned so much, with his family planning the now-memorial service that would be held on this same plaza.

His widow, Linda, took my arm and pointed to the statue. “You know we would get lunch and come park here,” in a lot alongside what’s known as Centennial Plaza, which also commemorates our century-mark a few years ago. “We would eat and watch as people would come walking by, and would stop to see the statue. To read about Jack, and what he went through.”

“How did he feel about that?”

She smiled at fond memories. “He would always seem so pleased.”

How honored I was to perform this service, and help his family in their time of grieving; how relieved I felt that Jack had lived to see this plaza made in his memory, that would last as long as the neighborhood as we know it endures.

Or at least as long as people like me seek to serve in a capacity that holds those who came before in a place of respect, while seeking to influence the flow of history in a manner that embraces the needs of the new, the mood of the surrounding community, and the trajectory of growth necessary to sustain the longterm health of a commercial district like Five Points.

I know the Colonel had these concerns in mind whenever he made decisions on behalf of the community; may I serve, clambering along wearing the size-too-big boots of courageous actors who trod the path into visibility well before me, in at least a dignified and honorable fashion as the man to whom this essay now pays tribute.

Rest easy, Colonel. If nothing else, I erected my own tribute to you in a passages of my own fiction. Here, a sample. May it please you to know I cared about you enough to put you into my work—I can make no higher tribute to my loved ones.

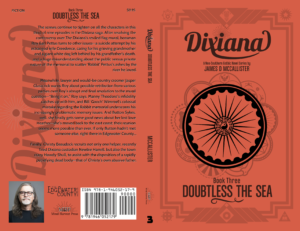

[From Dixiana Book Three: Doubtless the Sea]

[From Dixiana Book Three: Doubtless the Sea]

You recall sitting and listening to the Colonel, your personal, national hero, describe his experience in Vietnam. How the Vietcong tortured him.

“But they didn’t break me up here.” At this point in the telling, which you’ve heard several times, he always points to his temple. “My knees might be shot from the hard landing I took after my chute got tangled up in a tree and I had to cut myself loose. And my shoulder—boy, I tell ya. I still can’t raise this arm over my head,” demonstrating with a thick liver-spotted forearm lifted only to about the fourth rib. “That’s from where they hauled me up with my arms pulled back, left me hanging like that for hours. They didn’t get shit out of me. The rat-fuckers didn’t get inside my mind, either.”

“No?”

“Hell no, son—I walked out of that place with my shoulders back and head held high. It was February 1973, and I thought I might be dreaming. We were all standing on that transport in disbelief, laughing, crying, hugging, hooting, hollering. The pilot came on the intercom, ‘Gentleman, please, sit down! We’re going home!’ That only got us more stirred up. Shit, all of it’d been a waking nightmare, full of soup with monkey heads bobbing around in it, and cold, and heat, and insects. That torture, they didn’t bother with it for long. The rest of the time, we sat there. And maintained military decorum. And order. But most of all? Our dignity, Roy.”

“Nobody’s taking our dignity away. Are they, Colonel?”

He wrapped his cane against the concrete floor. “I tell ya, they tried, though. Those commie bastards. They took time away from us. But they didn’t strip of us of our patriotism, nor our sense of duty. They didn’t get near that, the little rat-eating sons of bitches.” His jowls jiggled and he lowered his voice. “Nixon, he should’ve dropped the bomb on them all. He would’ve, you know.”

“Jesus—you think?”

“He told me so, standing right there in the Rose Garden. ‘My hands were tied, boys, by all those hippie protesters in the streets, and by all the liberal cowards in the congress.’ A raw deal, that man. But not us. No sir. Don’t believe it for a minute.”

“You didn’t come home bitter?”

He scoffed, but his eyelids fluttered. “I would do it all again. And you would too, my boy, if the call to serve came your way.”

“I’d like to think so,” you tried to stammer.

“Of course you would. God bless our dear old country.”

You wish more than anything to have a talk with this real man’s man right now. But he ain’t here. He ain’t coming.

Or maybe he is, but you have your own pressing tortures to endure.

About dmac

James D. McCallister is a South Carolina author of novels, short stories, journalism, creative nonfiction and poetry. His neo-Southern Gothic novel series DIXIANA was released in 2019.

Thank you Don for sharing and how lucky we were to know and love such an incredible man.